The importance of hyper-parameter tuning

The goal of this blog post is to compare a machine learning algorithms, and demonstrate the importance of learning model complexity hyper-parameters, if the goal is to minimize prediction error (and that is always the goal in ML).

Theoretical discussion and visualizations

What is model complexity and why does it need to be controlled? Model complexity is the ability of a learning algorithm to fit complex patterns which are encoded in the train set. There is a different measure of model complexity for every learning algorithm:

- number of neighbors in K-nearest-neighbors,

- degree of L1 regularization in LASSO (as implemented in glmnet package in R),

- degree of polynomial in linear model basis expansion,

- cost parameter in support vector machines,

- number of iterations and learning rate in boosting (as implemented in xgboost package in R),

- number of gradient descent iterations (epochs), learning rate, number of hidden units, number of layers, etc, in neural networks.

In each machine learning algorithm, the model complexity must be controlled, by selecting a good value for the corresponding hyper-parameter. I created a data visualization which shows how this works using nearest neighbors (need to learn number of neighbors) and linear models (need to learn the degree of the polynomial basis expansion), for several regression problems.

- There are four different simulated data sets, each with a pattern of different complexity (constant, linear, quadratic, cubic).

- The linear model polynomial degree varies from 0 (constant prediction function, most regularized, least complex) to 9 (very wiggly prediction function that perfectly interpolates every train data point, least regularized, most complex).

- The number of neighbors varies from 1 (very wiggly prediction function that perfectly interpolates every train data point, least regularized, most complex) to 10 (constant prediction function, most regularized, least complex).

- These two learning algorithms are interesting examples to compare, because the least complex model (in both cases) always predicts the average of the train labels. That turns out to be the best prediction function, in the case of the constant data/pattern.

- But for the other data/patterns, a more complex regularization parameter must be used to get optimal prediction accuracy. For example, the regularization parameters which gives minimal test error for the linear data/pattern are 3 nearest neighbors, and polynomial degree 1.

The goal of this blog is to demonstrate how to use mlr3 auto tuner to properly learn such hyper-parameters, and show that approach is more accurate than using the defaults (which may be ok for some data, but sub-optimal for others).

Simulation

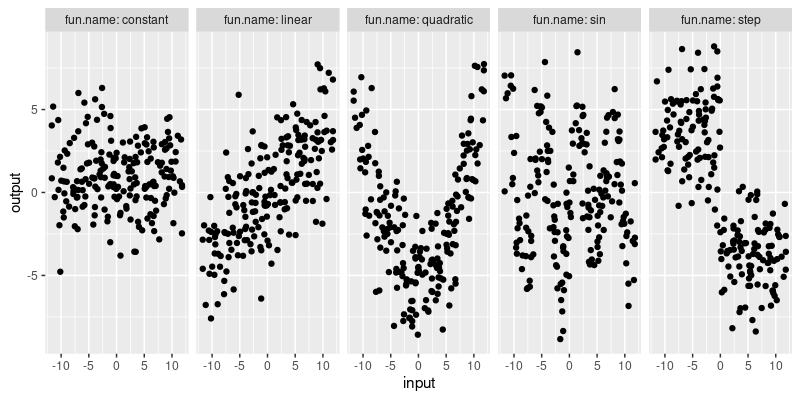

Below we define some simulated data, for five different regression problems, of varying complexity.

max.x <- 12

min.x <- -max.x

fun.list <- list(

constant=function(x)1,

linear=function(x)x/3,

quadratic=function(x)x^2/max.x-5,

sin=function(x)4*sin(x),

step=function(x)ifelse(x<0, 4, -4))

N <- 200

set.seed(1)

input.vec <- runif(N, min.x, max.x)

library(data.table)

task.list <- list()

sim.dt.list <- list()

for(fun.name in names(fun.list)){

f <- fun.list[[fun.name]]

true.vec <- f(input.vec)

task.dt <- data.table(

input=input.vec,

output=true.vec+rnorm(N,sd=2))

task.list[[fun.name]] <- mlr3::TaskRegr$new(

fun.name, task.dt, target="output"

)

sim.dt.list[[fun.name]] <- data.table(fun.name, task.dt)

}

(sim.dt <- rbindlist(sim.dt.list))

## fun.name input output

## <char> <num> <num>

## 1: constant -5.627792 -0.2407334

## 2: constant -3.069026 1.0842317

## 3: constant 1.748481 -0.8218433

## 4: constant 9.796987 1.3160575

## 5: constant -7.159634 -0.3091693

## ---

## 996: step 2.173756 -8.1816922

## 997: step -9.351345 7.3947878

## 998: step 8.172169 -1.8722377

## 999: step -4.368872 2.4667667

## 1000: step 6.788432 -3.2359849

library(ggplot2)

ggplot()+

geom_point(aes(

input, output),

data=sim.dt)+

facet_grid(. ~ fun.name, labeller=label_both)

The plot above visualizes the simulated data. The goal of each learning algorithm is to learn the pattern in each of the five different data sets. To do that, we define a few different learning algorithms in the next section.

Learning algorithm definitions

Perhaps the simplest learning algorithm is nearest neighbors, which can be implemented in the mlr3 framework using the code below.

nn.default <- mlr3learners::LearnerRegrKKNN$new()

nn.default$param_set

## <ParamSet>

## id class lower upper nlevels default value

## <char> <char> <num> <num> <num> <list> <list>

## 1: k ParamInt 1 Inf Inf 7 7

## 2: distance ParamDbl 0 Inf Inf 2

## 3: kernel ParamFct NA NA 10 optimal

## 4: scale ParamLgl NA NA 2 TRUE

## 5: ykernel ParamUty NA NA Inf

## 6: store_model ParamLgl NA NA 2 FALSE

The code above defines the default nearest neighbors regressor, which

has a default value of k=7 (that is the number of neighbors). As

discussed above, the number of neighbors is an important model

complexity hyper-parameter, which must be tuned for optimal prediction

accuracy. In other words, the default value 7 may provide sub-optimal

prediction accuracy, depending on the data set. Another option is to

manually select a different value for the number of neighbors, which

we do in the code below,

nn1 <- mlr3learners::LearnerRegrKKNN$new()

nn1$id <- "1 nearest neighbor"

nn1$param_set$values$k <- 1

The code above defines another nearest neighbor regressor, which uses 1 nearest neighbor, instead of the default 7. That may be better for some data sets, but in general, we would like to choose a different number of neighbors for each data set. We can do that using cross-validation, by dividing the train set into subtrain/validation sets, where the validation set is used to determine the optimal number of neighbors. The code below defines 5-fold cross-validation as the method to use,

subtrain.valid.cv <- mlr3::ResamplingCV$new()

subtrain.valid.cv$param_set$values$folds <- 5

Next, in the code below, we define a new nearest neighbor regressor, and tell mlr3 to tune the number of neighbors.

knn.learner <- mlr3learners::LearnerRegrKKNN$new()

knn.learner$param_set$values$k <- paradox::to_tune(1, 20)

To convert that to a learning algorithm that can be used in a

benchmark experiment, we need to use as the learner in an

auto_tuner, as in the code below,

knn.tuned = mlr3tuning::auto_tuner(

tuner = mlr3tuning::TunerGridSearch$new(),

learner = knn.learner,

resampling = subtrain.valid.cv,

measure = mlr3::msr("regr.mse"))

The code above says that we want to tune the learner using grid search, 5-fold CV, and select the model which minimizes MSE on the validation set.

Another non-linear regression algorithm is boosting, which can be

implemented in mlr3 using the code below. Again there are several

hyper-parameters which control model complexity, and in the code below

we tune two of them (eta=step size, nrounds=number of boosting

iterations). Note that some parameters should be tuned on the log

scale (like eta with log=TRUE in the code below), and others can be

tuned on the linear scale (like nrounds). Finally note in the code

below that we use a grid search with resolution 5 in order to save

time (default is 10 so with 2 hyper-parameters that would make 100

combinations, exercise for the reader to try that instead).

xgboost.learner <- mlr3learners::LearnerRegrXgboost$new()

xgboost.learner$param_set$values$eta <- paradox::to_tune(0.001, 1, log=TRUE)

xgboost.learner$param_set$values$nrounds <- paradox::to_tune(1, 100)

grid.search.5 <- mlr3tuning::TunerGridSearch$new()

grid.search.5$param_set$values$resolution <- 5

xgboost.tuned = mlr3tuning::auto_tuner(

tuner = grid.search.5,

learner = xgboost.learner,

resampling = subtrain.valid.cv,

measure = mlr3::msr("regr.mse"))

You might wonder about the code above, how did I know to tune eta from 0.001 to 1, and nrounds from 1 to 100? What are the good min/max values for each hyper-parameter? mlr3tuningspaces is a useful reference with data describing typical values for each hyper-parameter. And in fact, if you want to use the hyper-parameter ranges defined in that package, you can use code like below (ranger package for random forest).

ranger.tuned = mlr3tuning::auto_tuner(

tuner = grid.search.5,

learner = mlr3tuningspaces::lts(mlr3learners::LearnerRegrRanger$new()),

resampling = subtrain.valid.cv,

measure = mlr3::msr("regr.mse"))

Define benchmark experiment

After having defined the learning algorithms in the previous section, we combine them in the list below.

learner.list <- list(

mlr3::LearnerRegrFeatureless$new(),

mlr3learners::LearnerRegrRanger$new(), ranger.tuned,

mlr3learners::LearnerRegrXgboost$new(), xgboost.tuned,

knn.tuned, nn1, nn.default)

To see which of the learning algorithms is most accurate in each data set, we will use 3-fold cross-validation, as defined in ht code below.

train.test.cv <- mlr3::ResamplingCV$new()

train.test.cv$param_set$values$folds <- 3

In the code below, we define a benchmark grid, which combines tasks (data sets), with learners (algorithms), and resamplings (actually just one, 3-fold CV).

(bench.grid <- mlr3::benchmark_grid(

tasks=task.list,

learners=learner.list,

resamplings=train.test.cv))

## task learner resampling

## <char> <char> <char>

## 1: constant regr.featureless cv

## 2: constant regr.ranger cv

## 3: constant regr.ranger.tuned cv

## 4: constant regr.xgboost cv

## 5: constant regr.xgboost.tuned cv

## 6: constant regr.kknn.tuned cv

## 7: constant 1 nearest neighbor cv

## 8: constant regr.kknn cv

## 9: linear regr.featureless cv

## 10: linear regr.ranger cv

## 11: linear regr.ranger.tuned cv

## 12: linear regr.xgboost cv

## 13: linear regr.xgboost.tuned cv

## 14: linear regr.kknn.tuned cv

## 15: linear 1 nearest neighbor cv

## 16: linear regr.kknn cv

## 17: quadratic regr.featureless cv

## 18: quadratic regr.ranger cv

## 19: quadratic regr.ranger.tuned cv

## 20: quadratic regr.xgboost cv

## 21: quadratic regr.xgboost.tuned cv

## 22: quadratic regr.kknn.tuned cv

## 23: quadratic 1 nearest neighbor cv

## 24: quadratic regr.kknn cv

## 25: sin regr.featureless cv

## 26: sin regr.ranger cv

## 27: sin regr.ranger.tuned cv

## 28: sin regr.xgboost cv

## 29: sin regr.xgboost.tuned cv

## 30: sin regr.kknn.tuned cv

## 31: sin 1 nearest neighbor cv

## 32: sin regr.kknn cv

## 33: step regr.featureless cv

## 34: step regr.ranger cv

## 35: step regr.ranger.tuned cv

## 36: step regr.xgboost cv

## 37: step regr.xgboost.tuned cv

## 38: step regr.kknn.tuned cv

## 39: step 1 nearest neighbor cv

## 40: step regr.kknn cv

## task learner resampling

In the code below we tell the mlr3 logger to suppress most messages, then we run the benchmark experiment. Actually, if the results have already been computed and saved in the cache RData file, we just read that. Otherwise, you should run the code below that interactively, either on your own computer, or on a SLURM super-computer cluster. There are only 120 iterations in this case, but if you run that on a super-computer cluster, then it could potentially run 120x faster. It is better to use a super-computer for larger experiments, with more data sets, learning algorithms, and cross-validation folds. For example I have recently computed some machine learning experiments with over 1000 benchmark iterations, each of which can be computed in parallel (and very quickly using NAU Monsoon which has 4000 CPUs). See mlr3batchmark for computing these iterations in parallel using the batchtools R package (which supports backends such as SLURM, which is how things are parallelized on super-computers such as NAU Monsoon). See my R batchtools on Monsoon tutorial for more info.

lgr::get_logger("mlr3")$set_threshold("warn")

cache.RData <- "2024-01-29-hyper-parameter-tuning.RData"

if(file.exists(cache.RData)){

load(cache.RData)

}else{#code below should be run interactively.

if(on.cluster){

reg.dir <- "2024-01-29-hyper-parameter-tuning-registry"

unlink(reg.dir, recursive=TRUE)

reg = batchtools::makeExperimentRegistry(

file.dir = reg.dir,

seed = 1,

packages = "mlr3verse"

)

mlr3batchmark::batchmark(

bench.grid, store_models = TRUE, reg=reg)

job.table <- batchtools::getJobTable(reg=reg)

chunks <- data.frame(job.table, chunk=1)

batchtools::submitJobs(chunks, resources=list(

walltime = 60*60,#seconds

memory = 2000,#megabytes per cpu

ncpus=1, #>1 for multicore/parallel jobs.

ntasks=1, #>1 for MPI jobs.

chunks.as.arrayjobs=TRUE), reg=reg)

batchtools::getStatus(reg=reg)

jobs.after <- batchtools::getJobTable(reg=reg)

table(jobs.after$error)

ids <- jobs.after[is.na(error), job.id]

bench.result <- mlr3batchmark::reduceResultsBatchmark(ids, reg = reg)

}else{

## In the code below, we declare a multisession future plan to

## compute each benchmark iteration in parallel on this computer

## (data set, learning algorithm, cross-validation fold). For a

## few dozen iterations, using the multisession backend is

## probably sufficient (I have 12 CPUs on my work PC).

if(require(future))plan("multisession")

bench.result <- mlr3::benchmark(

bench.grid, store_models = TRUE)

}

save(bench.result, file=cache.RData)

}

If you are following along, now is the time to grab a cup of tea or coffee.

Comparing tuned to default/fixed hyper-parameters

After having computed the benchmark result in the previous section, we use the score method below to compute a data table with columns for train time and mean squared test error.

bench.score <- bench.result$score(mlr3::msrs(c("time_train","regr.mse")))

bench.score[1]

## nr task_id learner_id resampling_id iteration time_train regr.mse

## <int> <char> <char> <char> <int> <num> <num>

## 1: 1 constant regr.featureless cv 1 0.01 4.650449

## Hidden columns: uhash, task, learner, resampling, prediction

First, we create a new algorithm factor column in the code below, and take the subset of results for the nearest neighbors learning algorithms.

algo.levs <- c(

"regr.ranger.tuned", "regr.ranger",

"regr.xgboost.tuned", "regr.xgboost",

"regr.kknn.tuned", nn.default$id, nn1$id,

"regr.featureless")

only.nn <- bench.score[

, algorithm := factor(learner_id, algo.levs)

][

grepl("nn|featureless|neighbor", algorithm)

]

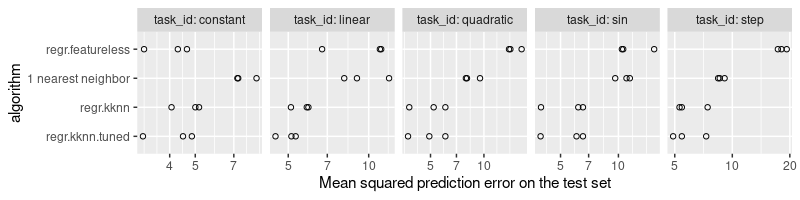

We use the code below to visualize the nearest neighbors test error values.

ggplot()+

geom_point(aes(

regr.mse, algorithm),

shape=1,

data=only.nn)+

facet_grid(. ~ task_id, labeller=label_both, scales="free")+

scale_x_log10(

"Mean squared prediction error on the test set")

The plot above shows the mean squared prediction error on the X axis, and the learning algorithm on the Y axis. The three versions of nearest neighbors are shown, along with the baseline featureless predictor (which always predicts a constant value, the mean of the train labels). It is clear that

- the 1 nearest neighbor algorithm is the least accurate learning algorithm, and sometimes even has larger test error rates than the featureless baseline (in the constant and linear data).

- the regr.kknn algorithm (default/fixed number of neighbors is 7) yields reasonable predictions, which are most of the time better than the featureless baseline (except in the constant task).

- the regr.kknn.tuned algorithm has the least prediction error overall, because it uses an internal grid search to select the best number of neighbors, as a function of the training data.

The code below computes the selected number of neighbors for the tuned nearest neighbor algorithms:

only.nn[

grepl("tuned", algorithm),

data.table(

task_id,

neighbors=sapply(learner, function(L)L$tuning_result$k))

]

## task_id neighbors

## <char> <int>

## 1: constant 16

## 2: constant 20

## 3: constant 20

## 4: linear 20

## 5: linear 20

## 6: linear 20

## 7: quadratic 9

## 8: quadratic 7

## 9: quadratic 12

## 10: sin 9

## 11: sin 9

## 12: sin 7

## 13: step 16

## 14: step 7

## 15: step 12

It is clear that the tuning procedure selected numbers of neighbors which are sometimes different from the fixed values we used in the other learners (1 and 7). As expected, we see larger number of neighbors for the simpler patterns (constant and linear).

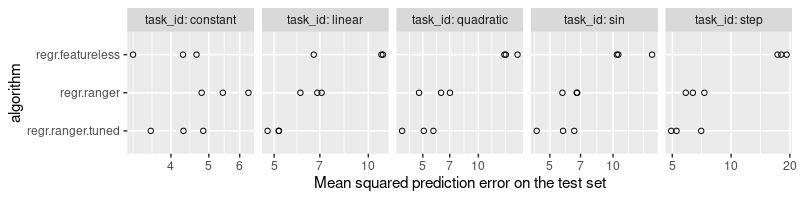

Next, we examine the test error rates of the random forest learners.

only.ranger <- bench.score[grepl("featureless|ranger", algorithm)]

ggplot()+

geom_point(aes(

regr.mse, algorithm),

shape=1,

data=only.ranger)+

facet_grid(. ~ task_id, labeller=label_both, scales="free")+

scale_x_log10(

"Mean squared prediction error on the test set")

It is clear from the plot above that the tuned version is at least as accurate as the default, for each data set. In the case of the simpler tasks (constant and linear), the tuned version is substantially better.

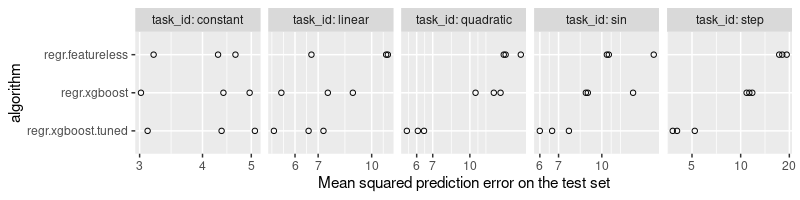

Next, we examine the test error rates of the xgboost learners.

only.xgboost <- bench.score[grepl("xgboost|featureless", algorithm)]

ggplot()+

geom_point(aes(

regr.mse, algorithm),

shape=1,

data=only.xgboost)+

facet_grid(. ~ task_id, labeller=label_both, scales="free")+

scale_x_log10(

"Mean squared prediction error on the test set")

The plot above shows that the tuned learner is at least as accurate as the default, for each data set. The tuned learner has significantly smaller prediction error for the more complex patterns (quadratic, sin, step).

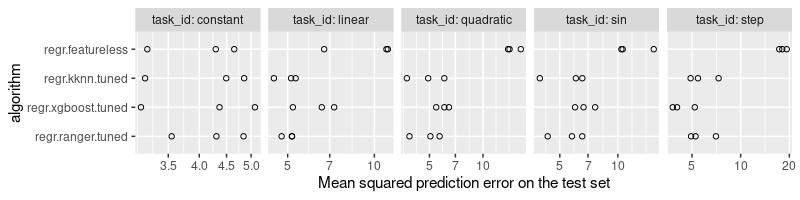

Comparing learning algorithms

In this section we compare the tuned versions of the learning algorithms with each other.

only.tuned <- bench.score[grepl("tuned|featureless", algorithm)]

ggplot()+

geom_point(aes(

regr.mse, algorithm),

shape=1,

data=only.tuned)+

facet_grid(. ~ task_id, labeller=label_both, scales="free")+

scale_x_log10(

"Mean squared prediction error on the test set")

The plot above shows that there is no one algorithm that is the best for every data set, which is to be expected (no free lunch theorem). The best algorithm for task=step seems to be xgboost, whereas the nearest neighbors and ranger algorithms predict with similar optimality on the other non-trivial tasks (linear, quadratic, sin).

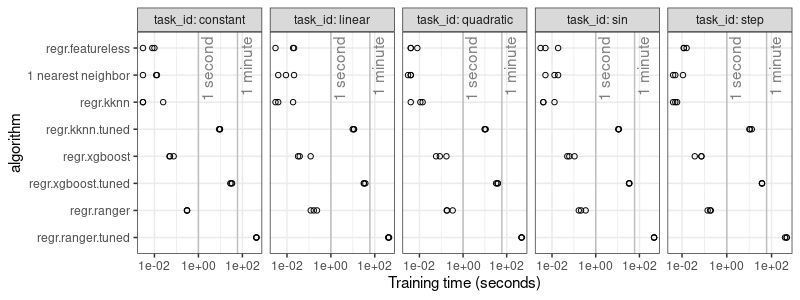

Comparing train time

In this section we compare the time it takes to train the algorithms.

ref <- function(seconds, unit){

data.table(seconds, label=paste0("1 ", unit, " "))

}

ref.dt <- rbind(

ref(60, "minute"),

ref(1, "second"))

ggplot()+

theme_bw()+

geom_point(aes(

time_train, algorithm),

shape=1,

data=bench.score)+

geom_vline(aes(

xintercept=seconds),

color="grey",

data=ref.dt)+

geom_text(aes(

seconds, Inf, label=label),

color="grey50",

data=ref.dt,

angle=90,

vjust=1.2,

hjust=1)+

facet_grid(. ~ task_id, labeller=label_both, scales="free")+

scale_x_log10(

"Training time (seconds)",

breaks=10^seq(-2,2,by=2))

It is clear from the plot above that the hyper-parameter tuning takes significantly more time than the learning algorithms with default/fixed hyper-parameters. This is to be expected, because an internal grid search needs to be computed, in order to determine the optimal hyper-parameters for each train set. The increased computation time is the price you have to pay for the increased prediction accuracy.

Conclusions

We have explained how to implement hyper-parameter tuning, in the context of the mlr3 framework in R. We have shown that hyper-parameter tuning takes more time, but results in consistently more accurate predictions, with respect to learning algorithms which use default/fixed hyper-parameters. We have additionally showed how to implement mlr3 benchmark experiments on a SLURM cluster using mlr3batchmark/batchtools packages.

Session info

sessionInfo()

## R version 4.3.2 (2023-10-31)

## Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu (64-bit)

## Running under: Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/blas/libblas.so.3.10.0

## LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/lapack/liblapack.so.3.10.0

##

## locale:

## [1] LC_CTYPE=fr_FR.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=fr_FR.UTF-8 LC_COLLATE=fr_FR.UTF-8

## [5] LC_MONETARY=fr_FR.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=fr_FR.UTF-8 LC_PAPER=fr_FR.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C

## [9] LC_ADDRESS=C LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=fr_FR.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

##

## time zone: America/Phoenix

## tzcode source: system (glibc)

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics utils datasets grDevices methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] future_1.33.1 ggplot2_3.4.4 data.table_1.15.0

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] future.apply_1.11.1 gtable_0.3.4 highr_0.10 dplyr_1.1.4 compiler_4.3.2

## [6] crayon_1.5.2 tidyselect_1.2.0 parallel_4.3.2 globals_0.16.2 scales_1.3.0

## [11] uuid_1.2-0 RhpcBLASctl_0.23-42 R6_2.5.1 mlr3tuning_0.19.2 labeling_0.4.3

## [16] generics_0.1.3 knitr_1.45.11 palmerpenguins_0.1.1 backports_1.4.1 checkmate_2.3.1

## [21] tibble_3.2.1 munsell_0.5.0 paradox_0.11.1 pillar_1.9.0 mlr3tuningspaces_0.4.0

## [26] mlr3measures_0.5.0 rlang_1.1.3 utf8_1.2.4 xfun_0.41.10 lgr_0.4.4

## [31] mlr3_0.17.2 mlr3misc_0.13.0 cli_3.6.2 withr_3.0.0 magrittr_2.0.3

## [36] digest_0.6.34 grid_4.3.2 mlr3learners_0.5.8 bbotk_0.7.3 lifecycle_1.0.4

## [41] vctrs_0.6.5 evaluate_0.23 glue_1.7.0 farver_2.1.1 listenv_0.9.1

## [46] codetools_0.2-19 parallelly_1.36.0 fansi_1.0.6 colorspace_2.1-0 tools_4.3.2

## [51] pkgconfig_2.0.3